The FT Tech for Growth Forum is supported by

Foreword

Jonathan Derbyshire, Tech for Growth Forum Editor, Financial Times

Economies across the developed world are facing labour shortages - especially of skilled workers. And the problem is particularly acute in the tech sector, and in the ever expanding number of jobs for which basic technological proficiency is a non-negotiable requirement.

This latest report from the FT’s Tech for Growth Forum examines the phenomenon in detail and asks not just how businesses and governments can bridge the technology skills gap, but also how they can use new technology itself as a tool to enhance the education and training that is fundamental to the challenge of getting fit for the modern digital economy.

Governments are beginning to acknowledge, first, that the digital literacy of the working population leaves a good deal to be desired and, second, that primary, secondary and tertiary education needs to be drastically overhauled in response. And businesses too know that the need to do more if they are to succeed in the increasingly competitive race for digital talent.

Technology and the skills shortage

More work but too few workers

Developed nations are facing a worker shortage. As pandemic restrictions have loosened, the demand for goods and services has rebounded but the supply of workers remains static.

In the UK, the US and the EU, vacancies have increased to match or outstrip the availability of people. In Britain this is most noticeable in the public sector, especially health and transport, but the shortage afflicts private companies too.

In February the British Chambers of Commerce reported the results of its 2022 survey of 5,600 firms. This showed that recruitment was harder than ever: nearly two in three firms wanted to hire people but eight in 10 of these said finding either skilled or unskilled workers was difficult.

The US has a similar problem. In November, Jay Powell, the chair of the Federal Reserve, said the labour force was 3.5mn workers shy of pre-pandemic forecasts. He said 2mn of the shortfall could be due to more people retiring early.

Job openings exceeded available workers by 4mn, equal to 1.7 jobs for each jobseeker. In March, the US Chamber of Commerce said the worker participation rate was 62.6 per cent, down from 63.3 per cent in February 2020. The reasons range from illness (an individual or family member) to low pay rates, to a desire to focus on acquiring more skills before re-entering the workforce.

Technology experts are in short supply everywhere but in America in particular the situation is acute, affecting tech businesses and those companies in other sectors that rely on an IT function.

The Computing Technology Industry Association, also known as CompTIA, is a nonprofit organisation that supports the US technology industry. It said that 9.1mn people were employed in technology in 2022 – six per cent of the US workforce. Some 61 per cent of that total were tech professionals such as software developers and network architects, while the others were in sector support roles.

Basic technological capability is essential for many workers. In the 12 months to August 2022, 10.7mn job postings required computer literacy in occupations from HR to nursing.

In Europe the battle for talent is no less severe.

Annabelle Gawer, director of the centre of digital economy at the University of Surrey, says the digital transformation has affected every company, blurring the line between tech and other sectors. She says that with hiring “there is no such thing as the tech sector anymore”.

In January a survey by the German Chambers of Commerce and Industry (DIHK) reported that more than half of 22,000 companies had difficulty hiring people. The situation was more extreme for technical businesses: two-thirds of groups in the electrical equipment, mechanical engineering and carmaking industries could not fill vacancies.

Another survey said the main personnel challenge for nearly a third of respondents was hiring. This situation was expected to continue for the next 12 months. The State of European Tech22 poll, compiled by Atomico, looked at more than 4,000 companies that had raised at least $500,000 from venture investors in the past year. On top of recruitment problems, as many as a quarter of companies expected talent retention to be an issue, up by 66 per cent on 2022.

In the UK the shortfall in tech talent was revealed in the 2023 Hays UK Salary & Recruiting Trends report. Data collated in late 2022 from 13,000 employers and professionals showed that demand for technology experts was expected to remain high. Almost all employers had experienced skills shortages in the past 12 months, and three-quarters had increased workers’ salaries. Despite this, nearly two-thirds of staff were looking to change jobs. Competition within such a small talent pool was a concern.

A spate of tech job losses — 200,000 worldwide and 16,000 in Europe last year, according to Atomico — gathered pace in 2023 but this had only a marginal effect on worries over the hiring squeeze.

Gawer says: “It may well be that because there has been so much laying off of workers in tech firms that the shortage may ease up a bit and these people find themselves working in other companies.”

Such reabsorption could mean that the effect of any excess headcount does not last long. Based on official releases, CompTIA estimates that tech unemployment lifted slightly from just below to just above 2 per cent in January 2023, compared with a rate of slightly below 4 per cent in the broader economy.

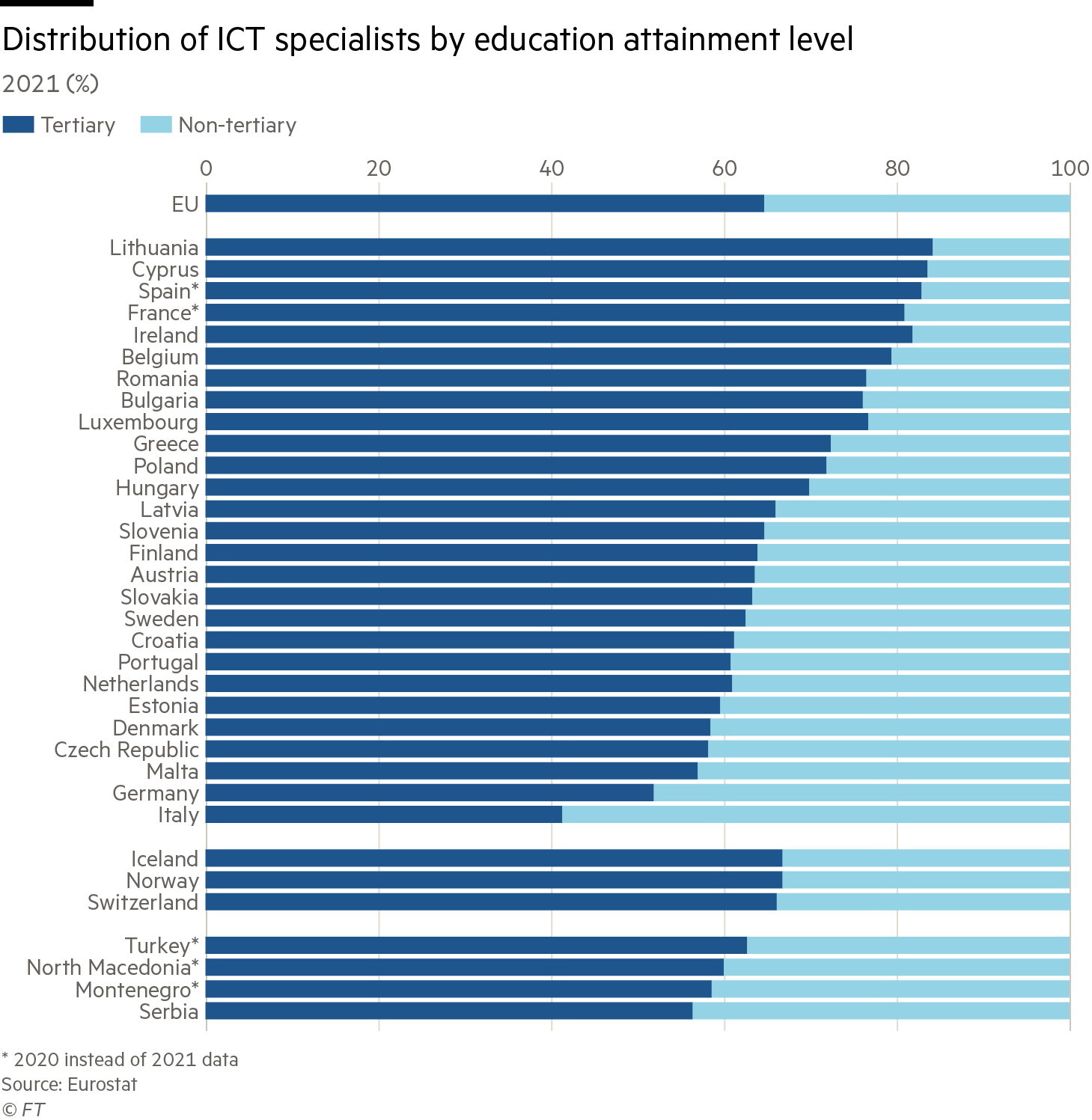

Long-term demand for tech talent is not expected to abate. Based on its digital ambitions the EU alone wants 20mn technology specialists, which compares with the 9mn it had in 2021.

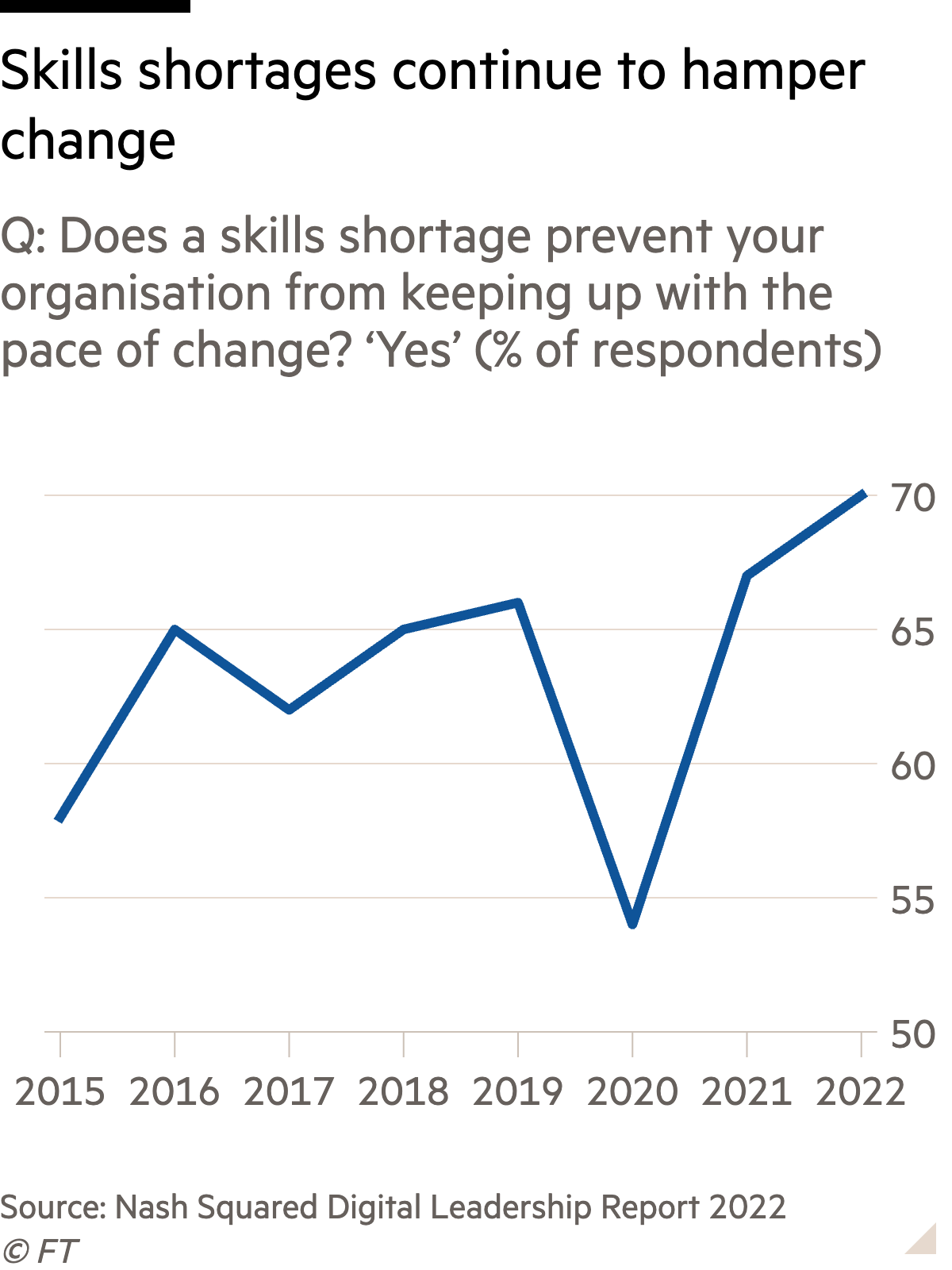

All countries aim to plug similar gaps, so importing specialists will be unsustainable. In 82 countries surveyed by Nash Squared for its Digital Leadership Report 2022, 58 per cent of tech company leaders expected their “skills needs” to increase while 70 per cent said a skills shortage was holding them back, the highest level in 24 years.

Pipeline problems

The problem is seeded at the early stages of education. The explosive growth of the digital economy has intensified competition for graduates in science, technology, engineering and mathematics (STEM), worsening the imbalance between supply and demand.

In Britain this feeds into the workplace at entry level. Adzuna, the job search engine, recorded the highest number of tech vacancies in 10 years between January and May 2022. More of these roles were at a senior rather than junior level, suggesting that workers had insufficient routes to gain the experience sought. With too few students taking Stem subjects, the problem is unlikely to improve quickly.

Government intervention

Ideally government policy would address the education deficit, especially as the UK aims to be a science and technology “superpower”. The skills gap is a long-running issue, as noted at a recent inquiry by the House of Lords.

One problem identified by Baroness Brown of Cambridge, who led the Science and Technology Committee inquiry, is the inadequacy of government oversight of its “huge numbers” of initiatives.

She says that without data to identify which line to pursue or discard, the government’s solution “seemed to be to add another initiative … We really need to do a much more thorough analysis of what has worked … and we need government departments to be working together on these things, not working against each other”.

Analysis may improve with the creation of the Unit for Future Skills within the Department for Education. Its job is to assess how to report jobs and skills data but this will take time. Time will also be needed to measure the progress of the Department for Science, Innovation and Technology, set up in February.

Policy seems similarly ineffective in the US even though the National Science and Technology Council has had a committee to monitor Stem programmes since 2011.

This issue is not unique to Britain and America. Nearly three-quarters of respondents to the Nash Squared survey said they “feel their government’s policies are completely ineffective in tackling the digital skills shortage”. The Asia Pacific region outperforms, however, with respondents four times more likely to have said that effective policies are in place.

More science for all

The technology skill deficit applies to broader populations too. Last year’s report on human capital by the European Commission said only 54 per cent of Europeans had at least basic digital skills, far short of the 2030 target of 70 per cent. In the UK, a Department for Education report in 2022 said that people now needed basic digital capability simply to interact in society.

The Royal Society, the oldest scientific academy in continuous existence, wants to see British children given a more “broad and balanced” education with maths and science “at the heart”. Witnesses to Brown’s House of Lords inquiry said coding was as essential as reading, writing and arithmetic for children aged 5-11.

As well as starting technical subjects earlier, some people believe learning should continue once formal education ends. In January Rishi Sunak, the prime minister, embraced part of this vision when he pledged to make maths a compulsory subject up to the age of 18. This promise will be hard to fulfil, however. The Association of School and College Leaders immediately pointed out that there were too few qualified teachers to meet even the previous targets.

Brown says too few maths and science teachers are university graduates of the subjects they teach, and that this often results in a lack of confidence and enthusiasm on the part of both teachers and students.

She says: “I think we have an ‘interest in the subject’ deficit which if we’re not careful starts at secondary school, where a lot of these subjects get taught by non-specialist staff.

“Teachers find themselves teaching right out of, potentially, their comfort zone, so it doesn't give young people a message that these are really exciting subjects — or important, for that matter.

“So then they gradually cut themselves off from being able to go on to A-levels and then to degree-level subjects. And of course if we don’t inspire them about science and technology, they probably cut themselves off from those apprenticeship routes as well.”

It doesn't help that while teachers are required to do teaching-related continuing professional development (CPD), there is no obligation to undertake subject-related CPD, even in areas as fast-moving as technology.

Technology as a tool

Learning to learn

The use of technology in education is now widespread, from basic tools such as video conferencing, which helps with lesson delivery, to AI programs that assist students to learn more effectively and enhance their grades. In the workplace, training and competency assessments are often carried out online, and communication tools improve collaboration and productivity.

Technology can also boost returns on formal learning. Obrizum, a Cambridge scale-up, uses AI to formulate personalised training programmes. These start with an assessment of a learner's knowledge and build up from there in a way that is unique to their progress. To eliminate guesswork, users not only have to pick the right answers but also to score their conviction level. This gamification of learning is more effective than any one size fits all training programme.

Such courses give companies data on what their employees know and how well they learn, and they reduce the time taken to achieve better outcomes. Workers’ knowledge can also be mapped against a company’s requirements. With good data, companies can find why certain employees do not perform well and change their processes to achieve better outcomes.

Rose Luckin, professor of learner-centred design at the UCL Knowledge Lab in London, carried out a study with a financial services company that trained traders. “They thought the reason so many traders left the business very soon after training was because they needed to do something about the training,” she says. “We were able to highlight the fact that the [problem lay in] recruiting the right people.”

With enough data, studies can also show how employees might be better at a different task, “so maybe they’re not going to be the best trader in the world but they might be great at compliance”.

Separately another university study revealed which teaching method — online or in person, for instance — worked well with different students and why. This allowed the university to decide when to intervene to make sure a student learns effectively. AI techniques such as process mining are among the technologies that can extract such data. Still “it takes a human to pull it together and say what it might mean”, Luckin says.

Man and machine

Better education about tech could solve two impediments to automation – lack of expertise and cultural resistance for fear of job losses – flagged up in the Nash Squared report. In the first, it needs to be broadly understood that technology is a supplement to human input, not a replacement, and in the second that training can help to reposition workers in roles where they can work with tech, not be replaced by it.

“We have to help people understand technology, and particularly AI, because it really is going to be part of their job whatever they do, whether it’s in a supermarket or on a farm,” Luckin says.

Despite misgivings, the use of digital labour has increased markedly in the four years to 2022, the Nash Squared data show. Machine learning and recognition software can be used in repetitive white-collar tasks such as document drafting, while manual labour – for example in warehouses – is being replaced by robotics.

Luckin focuses on the interface between AI and the white-collar worker, where productivity gains are significant. But she says we should not offload tasks just because we can. “We have to look very carefully at what the technology is good at doing and what the human is good at doing and work out where the sweet spot is, because that is where you increase productivity.

“ChatGPT does not understand anything it produces and to offload inappropriately to a tool that is so ignorant is dangerous.”

Areas where technology is better at a task than humans – processing vast quantities of data, for instance – are where it can be put to best use, but humans must be involved to understand the output.

The problem of ChatGPT

ChatGPT, a commercially-available AI chatbot, is upending education. While search engines called into question the value of learning facts – why should students remember them when they can use Google? – ChatGPT undermines the foundation of the education system.

“If an [artificial] intelligence can pass an assessment when it doesn’t understand a word it produces then that assessment is wrong,” Luckin says.

“You have to change the way the assessment is done,” she says, adding that ChatGPT could be incorporated if it is used to help students “make better judgments about what they believe to be true”.

How to get ahead in the hiring race

Think beyond Stem

Gordon Pelosse, senior vice-president of employer engagement at CompTIA, lays some of the blame for the technology hiring squeeze at the door of government.

He argues that the push to encourage more Stem students has had a detrimental effect. He agrees that having more Stem graduates is good, but young people now believe “you have to have strong Stem skills to enter tech — and it’s misleading”.

Pelosse says that widening the search beyond students focused on a career in technology — what he calls “tech intent” — to those with general “career intent” increases the number of potential candidates from 6mn to 50mn.

An obsession with qualifications has also skewed corporate hiring policies. Offering internships, apprenticeships or even on the job training to people without qualifications would provide a more sensible route to roles such as working on a help desk.

Companies that want to increase their options can do so with early intervention, with visits to schools to encourage students and parents to consider career opportunities.

This is especially relevant given that forward-thinking companies should look afresh at the type of people to hire. “We don’t necessarily need more tech workers in the traditional sense,” says Gawer of Surrey university. She believes that as consumer resistance to technology increases, perhaps due to concerns over job automation or surveillance, the demand will be for “bilingual” people who can operate in the technical world without being divorced from the rest of the enterprise.

She says: “I don’t think we need more coders because the coders themselves are going to be replaced by robots that can code. What we need is people who consider how technology is used: the commercial, legal, ethical and human resources implications.”

Luckin agrees. “I think we need to refine what we mean by technical skills. We need to include within that more interdisciplinary skills, more people who understand the technology and the way it impacts on humans.” She adds that the need is for people able to talk about technologies in non-technical ways.

Companies that fall behind in these areas will lose out with consumers, especially younger generations that place greater emphasis on values. They also run the risk of falling foul of regulators.

Think laterally

Besides anticipating a new type of technology worker and the skill sets needed, companies can also think laterally about where to find people with technical skills. In a twist used to entice the technology-savvy generation, TikTok has been involved in a campaign to recruit experts, such as gamers, who have less conventional training.

Use technology to help recruit

Technology can help with recruitment in other ways. In January, CompTIA launched a free tool developed with Lightcast, the labour market analytics provider. This optimises advertisements based on skills and outcomes rather than qualifications and inputs. The system can produce a posting that helps employers reach a far wider pool.

Pelosse believes it could be transformative. “Getting [technology employers] to use it is the next step. Part of that is the recognition of the need: trying to educate employers how they can have bias in their job posting inadvertently by picking certain schools, or how they can fall into the trap of using a degree as a proxy.”

Search for a minimum requirement, not a maximum

The advantage of looking at a wider pool cannot be emphasised too strongly. CyberUp, a nonprofit cybersecurity organisation, says 95 per cent of job openings require five or more years’ experience, while only 40 per cent of cybersecurity workers have been in the field that long.

Recruiting with a more open brief can open the door to greater diversity. Apprenticeships supported by the same organisation achieve better representation than industry averages across gender and ethnicity.

Champion apprenticeships

Apprenticeships are a viable route to filling roles. Nationalapprenticeship.org, a US project backed at the federal level, says that for every dollar invested in an apprentice the return is $1.47, plus a “public return” of $28. While Pelosse is pleased at initiatives that “chip away” at increasing apprenticeships, more could be done to make them widely available. “It’s a challenge,” he says. “American employers don’t see apprenticeships the same way that the UK and other countries see them.”

In Britain the House of Lords inquiry advised that apprenticeships should be more flexible in terms of the application process, giving workers the option to relocate and allowing the apprenticeship levy to be used by older workers for lifelong learning.

Such modifications could also benefit social mobility. In the same inquiry, Robert Halfon, the UK education minister, said that apprenticeships “solve so many problems”, notably helping people from disadvantaged areas “climb the ladder of opportunity”.

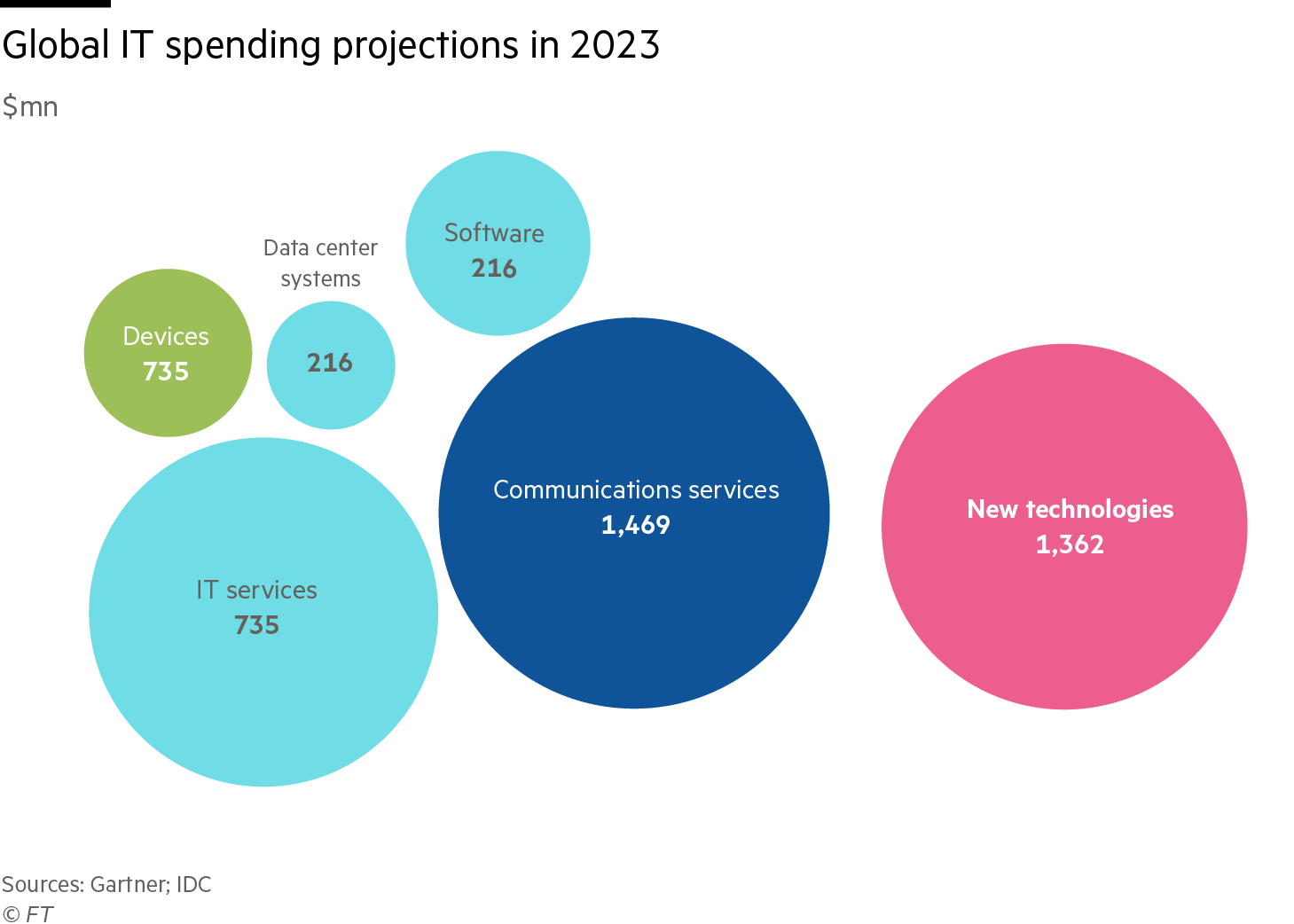

Let people learn on the job

According to the Financial Times nearly $400bn a year is spent globally on training. Informal or on the job learning is not valued despite more than 70 per cent of workers participating in it. This compares with 41 per cent in non-formal training and just 8 per cent in formal training. It is also beneficial for the employer, which is great news for UK companies that collectively invest only half the EU average per worker. The OECD reckons that an hour of informal learning costs $15.50 for an annual return of $55. Formal training lasts longer but involves fewer people. Northern Europe and New Zealand offer the most training of any kind.

Upskill (bring back the old?)

Even with the benefits of informal learning, formal training cannot be ignored. According to McKinsey research as many as 375mn workers globally may have to change their occupations in the coming decade, making retraining an essential consideration (on the upside, automation could free up nearly a third of their time for new work).

Investment in training brings benefits to companies beyond those that are experiencing significant change. A 2018 study by LinkedIn found that 94 per cent of employees would stay at a company longer if it invested in their careers. Younger generations in particular want an employer that cares about wellbeing.

Training is key to keeping a productive workforce and it can be less costly than hiring. According to the World Economic Forum, it would be cheaper to reskill a quarter of all workers in at-risk jobs in the US than it would be to find new ones; this is based on financial considerations alone, never mind societal and other effects. Collaboration such as pooling industry resources could lift this proportion to half of the workforce.

CompTIA may provide an example of how this can be done. The organisation makes use of professionals’ experience of given roles to create training programmes. “There is a job task analysis and then we create questions that test knowledge around the functions of that job,” Pelosse says. “Member partners provide the expertise to tell us what those people that work in that job everyday need to know.” The partner programme has given 3mn certifications to 2mn people.

The carrot of education could be especially useful in enticing opted-out workers to return to the jobs market, especially as many Americans currently outside the workplace give “learning new skills” as a reason.

Recruit overseas

One in five companies have looked to recruit overseas because of a shortage of talent at home, according to Remote, the global talent consultant, which polled 1,400 hiring managers. In the UK this strategy may be working if statistics on the post-Brexit immigration of skilled workers are a guide. This is not a long-term solution, however. As Brown points out, “we can’t go on pinching” other countries’ talent indefinitely.

Final cautions

While communication platforms can aid collaboration and inclusivity, they may also increase inequalities, possibly due to a lack of connectivity or literacy.

As ever, cybersecurity is a risk. A 2022 report by ISC2 flags up the shortage of expertise. The global cyber security organisation says there are 4.7mn cyber security experts but 3.4mn more are needed. This is not an area that companies can afford to ignore.

It is no longer sufficient simply to be able to operate basic hardware. In an increasingly digital world, people need to be taught about tech's limitations as well as how they, personally, can be manipulated by the machines they use to connect and entertain themselves.

Gawer warns that it is dangerous to rely on technology without understanding the tricks used by companies to foster such reliance. “The man or the woman on the street needs to understand enough about how technology works so that they keep a sense of agency and sovereignty in decision-making,” she says.

Studies are only as good as the questions asked and the quality of the data used. Companies that want insights into their employees and processes must spend time to decide on the right questions as well as to source and clean the data.